13 Dec Cholera Prevention and Safety in High-Risk Areas: A Guide From International SOS

Cholera remains a significant public health challenge in Nigeria and across many African countries due to inadequate access to clean water and sanitation facilities. During the rainy season, which usually lasts from May to October each year, Cholera risks worsens due to flooding which can contaminate water sources and destroy water and sanitation hygiene (WASH) infrastructures.

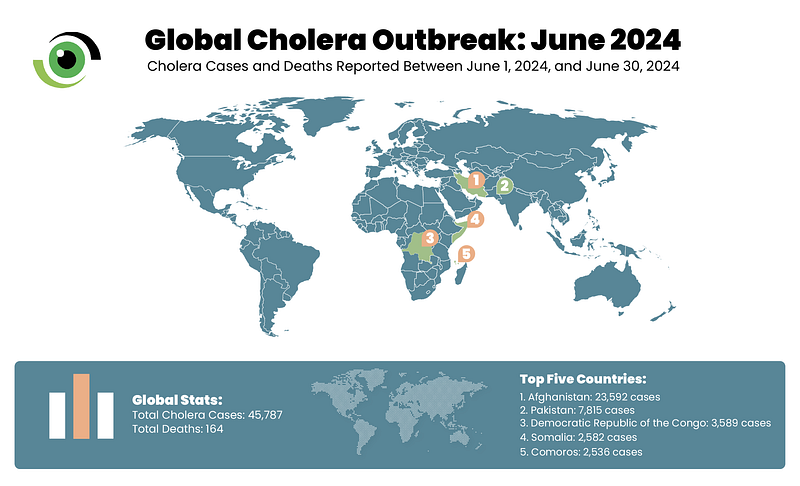

Between January 1, 2024, and July 28, 2024, the World Health Organisation (WHO) reported a total of 307,433 cholera cases and 2,326 deaths across 26 countries spanning five WHO regions. Notably, the African Region accounted for the second-highest number of cases, surpassed only by the Eastern Mediterranean Region, highlighting the significant burden of cholera in these areas.

In this interview, Dr Chris van Straten, global health advisor on clinical governance at International SOS, offers insights into the current state of the Cholera across Africa and the ways travellers to high risk areas can protect themselves.

International SOS is a global medical and travel security services company providing emergency assistance to individuals, organisations, and governments including medical assistance, travel security, health consulting, emergency response, and travel risk management.

Can you please give us the current state of the cholera outbreak in Africa, especially in Nigeria, which is currently is in its rainy season?

Dr Van Straten: “Globally, we have seen an increase in cholera cases. So it is not just in Africa, but also in many parts of Asia. There are many reasons for this, and some of them will vary depending on the country, the location, and the unique challenges in their countries.

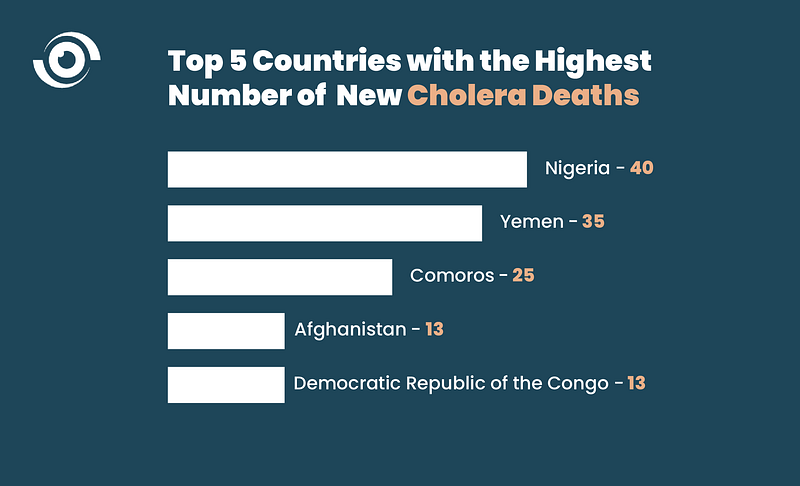

In Africa, there has been an estimated 381,000 cases of cholera, and that’s mostly in 13 countries, with about 6,733 deaths. Zimbabwe is on the list [as well as] Mozambique, Malawi, Ethiopia, Congo, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Nigeria has endemic cholera, when it is dry season, the numbers tend to be a bit lower, when it’s the wet season, [cases] go up.

In Nigeria, [Cholera cases] might be slightly higher because in the last update that I saw, there were over 3,600 suspected cases and approximately 103 deaths. The fatality rate was sitting at about 2.8%, but that could change depending on the area.

Another factor is, if there are no good sanitation and the removal of waste, especially in the poorer areas. Maybe [due to] defacating in bushes or the [use of a] latrine system. When people use a pit latrine that is not very deep or it’s not well constructed, significant flooding can wash up faeces which can deposit the cholera bacterium into water sources. That is where people often [get infected] when using rivers or contaminated sources to prepare food or for their drinking water.”

Why is the rate of this outbreak higher in some countries than in others?

Dr Van Straten: “Having spent many years working in the densely populated, low-income areas of South Africa, including slums and shanty towns, I’ve witnessed firsthand the [health] challenges faced by these communities. As a junior doctor, my experiences, particularly in a project I led nearly 20 years ago, have given me valuable insight into the complex issues affecting these areas and inform my understanding of the present day.

So the people who are most at risk of outbreaks such as Cholera are in [densely populated] countries where you don’t have running tap water or water systems that are not processed to a high standard or they don’t have good sewage and sanitation to remove faeces and defecation basically. So those communities are already at higher risk.

Poverty also places [some countries] at risk, and then what’s interesting is how elements of climate change are starting to impact countris more and more. I’m going to give you an example. Malawi has seen sporadic cholera outbreaks and they’ve usually been seasonal but they’ve usually been able to contain them but about 18 months back, there was this big tropical storm, one of the biggest tropical storms and it hit Malawi twice. That storm devastated the water supply [and destroyed] parts of the sewage systems. It triggered outbreaks and thousands of people got infected.

Malawi is still trying to get it under control, I think they are now finally getting a hang of it. So that’s why countries like Malawi and many countries in Africa with this high density, limited infrastructure and being battered by these big storms may have reoccurring outbreaks more than others.”

Can you talk more about how people can protect themselves in high-risk areas?

Dr Van Straten: “The first step is access to data and there are many African health institutions and laboratories that are currently tracking the number of cases in collaboration with Africa Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) and WHO Africa.

So if when we are thinking about risks, [it] will differ from person to person. Let me give an example, let’s say you are a businessman or businesswoman and you are in South Africa and you want to travel to Malawi or you want to travel to Nigeria. The first thing you should do is to access the data. I work for company called International SOS and we have got a service that tracks and monitors outbreaks in different countries. So that’s one source. I personally also go to WHO.

So if you’re traveling to a hotspot or a country where there’s an outbreak, do your homework, check several resources. And what I make sure is where am going to be staying? Where am I going to get my food? Where am going to get my water? For example, I won’t be getting food from any vendor if I am not confident that they have good hygiene and if I don’t know the quality of the water that they use. Even if you have a salad or a fruit and you wash the fruit but that water was contaminated that would mean contamination and you can pick up Cholera. So when traveling, I always do a double check on where am I going? What’s the current status in terms of cases and numbers? Source of water. If I’m in doubt, I can boil my water for a minute and then put it in a cup, let it cool down and use that for my drinking or for brushing my teeth or for washing my face.”

What precautionary measures need to be taken by countries to address yearly outbreaks?

Dr Van Straten: “There are a lot of measures that need to be taken. I am going to quote from the WHO, ‘Cholera is both a health problem and a socio-economic development challenge,’ so a multi-sectoral response is required. The long-term solution for Cholera control lies in economic development and universal access to drinking water and basic sanitation.

Health authorities [can also] report to their local municipalities and to the Ministries of Health so that people are informed about the hotspots [of the outbreak].

Also, educating and supporting health care professionals on how to contain the outbreak without getting infected. We must also ensure that vaccines are being administered in the communities where outbreaks occur and to healthcare professionals.

Currently, the WHO, the Africa Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), and all these different ministries of health are increasingly supporting one another. This is where I’m getting also quite excited. Gavi has put agreement in place with the different health ministries to create more vaccine capacity in Africa and this is off the back of what we saw during the COVID-19 pandemic, where there was such a big shortage of life-saving vaccines in the developing world, especially parts of Africa.”

With a wealth of experience spanning over eight years, Dr. Chris Van Straten, a renowned medical director and global health advisor, delivers vital guidance and support to healthcare professionals working in demanding settings, such as offshore platforms, mining operations, and humanitarian crises.

No Comments